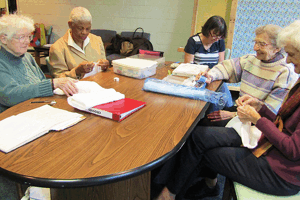

Lucy’s Sewing Group meets Fridays to carry on an embroidery tradition. From left: Rita Cyr-Bonga, Jean Davies, Diane Radford, Ann Dalzell and Flo Harvey. ~ McKnight photos

By Gisele McKnight

Every Friday morning, between three and seven women gather at Cathedral Memorial Hall to keep alive the art of ecclesiastical embroidery.

They range in age from their early 60s to late 80s and they call themselves Lucy’s Sewing Group, based out of Christ Church Cathedral.

Together they have a few hundred years of sewing experience. Without them, and others like them, our Anglican church services would be hard pressed to function.

Their ministry is the embroidery of altar linens — corporals, credence cloths, fair linen, purificators and so on. Without purificators, for example, how would a priest celebrate Holy Eucharist?

“It’s definitely a ministry,” said Rita Cyr-Bonga. “It’s very important. I can’t put it into words.”

“From my point of view, I can sew, so I regard that as a gift. Therefore I should use it,” said Ann Dalzell, another of the members.

Production

The process of producing an embroidered cloth begins in Ireland at Ulster Weavers. Lucy’s buys it in a 10-metre roll. They tried the locally available linen, but it didn’t measure up, so they stick with the Irish.

Rita Cyr-Bonga rolls up a measuring tape after working with a bolt of Irish linen. Lucy’s Sewing Group doesn’t use the cathedral kitchen for eating, only for laying out and cutting metres and metres of linen.

Once it arrives in Fredericton, Rita takes it home for preparation.

“It has to be laundered, washed and ironed, before we use it,” said Jean Davies, who acts as the organizer of the group. “Imagine washing your tablecloth, but 10 metres of it. It’s not a job I would say ‘let me do it!’”

Laundering is to prevent shrinkage later on. Measurements for their products are precise, so this step is crucial.

Then it’s time for cutting the linen into the pieces for which they have orders. Once that’s done, the pieces are hemmed with mitred corners. Then finally, the embroidery can begin.

Flo Harvey explains the process: Fold the cloth in half to find the centre line. Stitch a blue line along it. Fold it the other way and repeat.

“When you’re finished, you have a cross in the centre,” said Flo, adding that’s where the embroidery will go.

A design is selected — either from their catalogue or one the customer provides — and the linen is placed over the pattern for tracing. Flo uses a light table at home and a washable ink pen to do the tracing. Then it’s ready for embroidery, once those blue stitch lines are removed.

When the embroidery is complete, it’s time for another laundering and ironing, and delivery to the customer.

While the group meets and sews each week, much of the work is done at home.

Output

Lucy’s produces altar linens for the diocese, and as time and hands permit, they take on projects from elsewhere, even from as far away as the United States on occasion. They made four altar cloths for the Cathedral’s mission to a church in Belize, for example.

In an average year, the group will produce 40-50 purificators, five corporals, five fair linens, two credence cloths and two stiff palls. Turn around time is two months to several months, depending on the workload.

“We have a waiting list and we just do it as we go,” said Jean.

Their price list hasn’t changed in a long time. A purificator is $12.50; a fair linen (altar cloth) is about $250. The latest roll of linen cost $306 Cdn, and fortunately, church linens are duty-free.

Their profits are donated to a variety of charitable causes.

Just a spark

Repair of altar linens is a tricky business. If a stitch is loose on a hem, it can be mended. But if it’s a hole in the cloth, its usefulness has ended.

“Traditionally we don’t mend altar linens,” said Ann. “There can be no broken threads on the altar. The only exception is hems.”

That’s why it’s important to snuff a candle, not blow it out. A spark can make a hole, and the only method of disposal is to burn it.

Lucy’s origins

In an earlier era, ecclesiastical embroidery involved silk and gold threads on silk cloth. Some churches in the diocese still have these treasures. Now, however, the work of Lucy’s is white on white — white thread on white linen.

Ann, though, had the privilege of restoring Margaret Medley’s colourful embroidered frontals at Trinity Church in Dorchester about five years ago.

“The whole tradition started with Margaret Medley,” said Ann. “By the time she was in the country 12 months, she had started an altar guild.”

Margaret was the wife of Bishop John Medley.

Lucy’s Sewing Group, though, is not part of an altar guild. The roots of this group lie with Lucy McNeill, a somewhat stern but gifted embroiderer who lived next door to Cathedral Memorial Hall.

“Lucy was a rather formidable person,” said Ann. “People don’t realize she was very keen to get small group sewers going in our parishes. Lucy has had a terrific impact.”

Lucy once wrote a front-page article for Embroidery Canada, after which the magazine asked her to continue contributing.

Her answer: ‘I am not at all interested in domestic embroidery.’

She did, however, author a 32-page book called Sanctuary Linens, Choosing, Making and Embroidering, published by the Anglican Book Centre in Toronto in 1975. Two editions were published, but it’s rare to find one these days.

Some in the current group worked with Lucy.

“We were doing this work under her helpful hand and met at her house once a week,” said Ann. “We just kept on afterwards.”

Lucy died several years ago.

New members welcome

Jean was recruited about 15 years ago by the dean’s wife.

“She said, ‘You sew. Why don’t you join Lucy’s group?’ I didn’t know what Lucy’s group was.”

Diane Radford is one of the group’s younger members. She has a unique perspective as a member of the sanctuary guild.

“I find it interesting to see the other side of it,” she said. “You have no idea of the work that goes into it until you see this.”

While some might think the embroidery is too intricate or difficult, it’s a craft that can be learned, and the women at Lucy’s are eager to share it. They eagerly welcome new members. And because this group is senior in age, they understand the importance of recruitment.

To contact the group, call Cathedral Memorial Hall: 450-8500.

Re-posted from the Diocese of Fredericton: The art of ecclesiastical embroidery 27 September 2016